In a recent literature review by Puzziferri and colleagues in Journal of the American Medical Association, the current status of long term high quality data in bariatric surgery research was assessed. They examined the literature to see just how much high quality longer term data is out there (defined as studies of 2 years or more, with follow up data on at least 80% of patients by the 2 year mark).

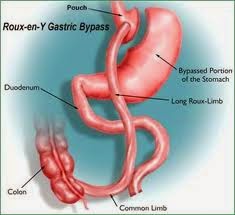

They found that only 29 studies total (less than 3% of studies identified) had 80% or more of patients followed up past the 2 year mark (7,971 patients total). On analysis of available data in these studies, they found that the average excess weight loss was 66% for gastric bypass surgery, vs 45% for gastric band. Type 2 diabetes remission rates (based on 6 studies) were 67% for gastric bypass, vs 29% for gastric band. Remission of hypertension (high blood pressure, based on 3 studies) was 38% for gastric bypass and 17% for gastric banding. There wasn’t enough data to analyze these parameters for sleeve gastrectomy. No study had data past 5 years. Concerningly, only half of the studies reported on complications at least 2 years after surgery.

So, while the existing high quality long term data is encouraging, we are still lacking in quantity of good quality data (clinical trials with low long term dropout rates) to have a thorough understanding of long term effects of bariatric surgery. While we do have encouraging observational studies to guide us on longer term benefits vs risks of bariatric surgery (encouraging particularly for gastric bypass surgery and sleeve gastrectomy), randomized controlled clinical trials ideally need to be done and patients followed long term (with less dropouts) to have a more comprehensive understanding of long term effects.

The above being said – as discussed in a recent study by Courcoulas and colleagues, and as I can certainly attest to from my own research experiences – this is a tall order to fill.