Another interesting approach to less invasive obesity/metabolic surgery that is currently being studied is the duodenal-jejunal bypass liner. This is a temporary 60-cm liner that is delivered into the upper part of the small intestine endoscopically (ie, by putting a camera and insertion equipment down through the mouth). It is left in place for a number of months, and then removed. It’s sometimes referred to as the ‘duodenal condom’ in that… well, you can see the resemblance… but both ends are open to allow food to pass through.

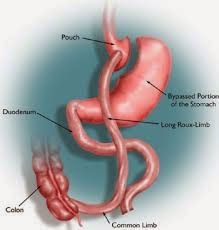

The idea behind this is to mimic (in a shorter version) the intestinal component of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, where the intestines are surgically rerouted to bypass about the first 150cm of small intestine. We think (based on studies) that one of the major reasons why type 2 diabetes often improves dramatically after gastric bypass surgery is the hormone changes that happen when the intestine is rerouted in this fashion; therefore, there is a lot of interest in seeing whether the liner would have an effect not only on weight loss, but also on type 2 diabetes.

Gastric Bypass Surgery

A clinical trial was recently done on the liner, where 77 patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity were randomized to receive either the liner, or dietary counselling (control group). After 6 months, patients who had the liner had greater weight loss, better diabetes control, and required less diabetes medication than the control group.

Patients then had the liners removed, and both groups were followed up for an additional 6 months after liner removal, with 66 patients completing the full study. There was some weight regain in the group who had previously had the liner, though at 1 year they still had greater weight loss than the control group. At 1 year, there was no longer a difference in diabetes control between the groups.

In the short term, it appears that the liner is quite effective to help people lose weight and improve their type 2 diabetes control. However, removal of the liner has to happen at some point, because the longer the liner is left in, the higher the risk that it can lose its hold and migrate further down the intestine, or cause bleeding or perforation (a hole in the intestinal wall), which are all serious complications. So far, the liner has been shown to have a low risk of these complications after 6 months, and a few studies have now been published suggesting the risk is also low after 1 year.

The liner’s current temporary nature is reminiscent of many of the ‘diets’ out there – they do nothing to help make permanent lifestyle changes, so after the diet (or the liner) is gone, the likelihood is that weight will be regained, along with its metabolic complications. It would be interesting if the liner could be left in safely for a longer period of time – I’ll be watching this area with interest, as the duration of study is growing. In the meantime, while the liner’s results look good in the short term, I’m not overly enthusiastic about an intervention if it is only temporary.