Over the last several decades, we have seen the average age of first period (called menarche) decrease by 1-2 years. The prevalence of girls in USA having early menarche (before age 11) has also increased from 2.6-4.6% to 6.6-12.2% over the last 60 years. Understanding why periods are starting earlier is important as it can be distressing for these young girls, and is also associated with a higher long term risk of breast cancer, depression, and metabolic risk factors including type 2 diabetes and obesity.

While some of the trend towards earlier periods over the last several decades is due to better health and living conditions, it is also increasingly recognized that environmental factors including weight gain in pregnancy and energy availability during fetal life and early childhood may play an important role.

A recent review published in Obesity Reviews summarizes the currently available data on this topic. While it reveals that the literature on this topic is complex, challenging to interpret, and even contradictory at times, the overarching conclusions were that there may be a higher risk of a girl having an early first period when her birth weight is lower, and with higher body weight and weight gain in in infancy and childhood.

So why would energy availability/energy stores have an influence on age of first period? Here are some possible links:

1. Leptin,

which is a signal of energy availability produced by fat tissue, is elevated in obesity, and also in children with low birth weight experiencing catch up growth. Leptin is thought to be necessary for the onset of puberty, so higher leptin may stimulate earlier puberty.

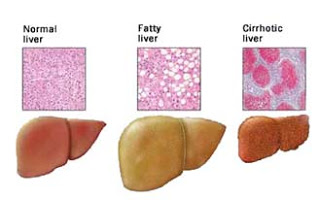

2. Fat tissue converts testosterone to estrogen (and vice versa). Rapid weight gain and childhood obesity is associated with greater production of testosterone derivatives from the adrenal glands, so there may be more of this testosterone available to convert to estrogen in fat tissue, contributing to an earlier first period.

3. Increased insulin levels (as seen in obesity) may advance sexual maturation; in fact, there is some evidence that metformin, a diabetes medication that lowers insulin resistance, may delay onset of periods in low-birth-weight girls with early onset of puberty.

4. Genes have been discovered to be associated with both obesity and age of first period, suggesting there may be some common genetic threads

here too.

Also interesting:

5. Nutritional factors. Breast feeding, and higher intake of plant proteins and fibre may be protective of excessive weight gain and thus protect against earlier periods. Formula feeding and high intake of cow’s milk and animal protein is associated with an earlier first period (possibly by stimulation of IGF-1 secretion, thus triggering earlier growth). Higher sugary beverage consumption is also associated with earlier periods, independent of body mass index (BMI).

6. Chemicals in our environment that mess with our hormone systems (called endocrine disruptors) may modify age of first period directly (by modulating hormone responsiveness, epigenetic effects, or stimulating

maturation directly), or indirectly by increasing the risk of childhood obesity.

So, it seems that prenatal life, infancy and childhood may present opportunities to improve overall health, and thereby possibly prevent early onset of menstrual periods.

This includes:

- Ensuring appropriate nutritional status of mom while pregnant

- Watching for suboptimal fetal growth (and managing appropriately depending on cause)

- Watching for, and managing, excessive weight gain in childhood

- Watching for signs of early pubertal development and intervening where appropriate with lifestyle/weight management strategies. I would be very curious to hear from my pediatric colleagues whether they are using metformin in this scenario – please contribute your comments at the end of this blog post!

Follow me on twitter! @drsuepedersen