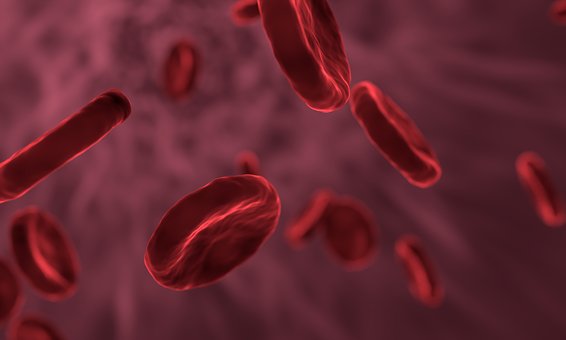

We know that having enough iron is important for production of red blood cells, and we know that iron deficiency anemia should prompt a search to rule out sources of blood loss, for example colon cancer. What we don’t pay enough attention to is the health consequence of having too much iron in one’s body – which may be much more common than we think.

While the amount of iron absorbed from the diet should be tightly regulated by our body, people who carry the gene responsible for a condition called hemochromatosis can have too much iron on board, because the body is not able to regulate well and ends up absorbing too much iron. You need two copies of the gene (one from each parent) to have full blown hemochromatosis, which is present in 1 in 200 people in USA. The iron overload in hemochromatosis can have many adverse health consequences, including liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, heart failure, diabetes, arthritis, testicular failure, and hypothyroidism. Hemochromatosis is usually treated in a very straightforward way – phlebotomy – removing some blood at intervals to decrease the iron levels in the body.

While we used to think that carrying one hemochromatosis gene is harmless, more recent research suggests that carriers of the gene have modest elevations in iron stores as well. Current estimates suggest that up to 30% of the US population is a carrier for the hemochromatosis gene. Studies have also shown that carriers have a higher risk of heart disease and stroke as well as colon cancer, breast cancer, hematologic malignancy, Alzheimers, and Parkinson’s disease.

A person may also think that if they don’t eat much red meat, they couldn’t possibly be at risk of iron overload. Think again – many food items are fortified with iron, and surprisingly, a food as benign sounding as breakfast cereal may be giving you more than you need.

Assessment of iron status starts with a blood test to measure ferritin levels. Ferritin is a marker of iron stores, so if it is low, then that person is likely low in iron. If ferritin is elevated, it can mean that there is too much iron on board, but ferritin is also what we call an ‘acute phase reactant’ – meaning that it can be temporarily elevated during times of illness or inflammation as well. Additional iron studies (also blood tests) can be done including measurement of iron, transferrin saturation, and total iron binding capacity, to get a better understanding of the true iron status.

More research is clearly needed to better understand the relationship of high iron levels and disease; the role of the hemochromatosis gene; and whether treatment (ie, phlebotomy) can decrease or improve these health issues.

And importantly, there are many people out there with the opposite problem of being deficient in iron, in which case it is important to not only figure out what is causing the iron deficiency, but also to treat it appropriately. Too much iron is not good, but too little iron is not good either.

A huge thanks to my friend and colleague Pam for giving me the heads’ up on the well referenced article written by an ER resident in Boston, which inspired me to write this blog post.

Dr Sue Pedersen www.drsue.ca © 2019

Follow me on Twitter! @drsuepedersen