Many people who seek bariatric surgery have multiple health conditions associated with their obesity, often requiring them to take many medications. While many of these health conditions can improve markedly after surgery, many people still need to take several medications over the long term after surgery (and they may have other unrelated medical issues also requiring oral medication). Because the intestinal anatomy is altered with bariatric surgery, an important question is:

What happens to the absorption and effect of medications after bariatric surgery?

There are many ways that bariatric surgery could impact absorption and/or bioavailability of medications, including:

- Increased pH in the stomach

- Faster transit of medications from stomach to small intestine

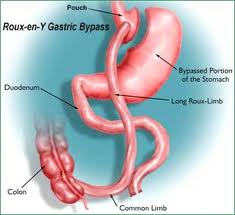

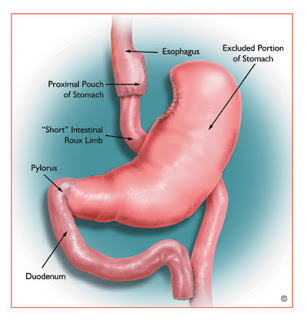

- Skipping metabolism and absorption in the first part of the intestine (gastric bypass surgery)

- Changes in intestinal motility (which could for example affect absorption of slow release formulations)

- Weight loss after surgery decreasing total body inflammation (thereby potentially improving the function of enzymes that metabolize medications)

- Weight loss after surgery decreasing the amount of body mass for medications to distribute through

- Improvement in fatty liver disease (thus better ability to metabolize medications in the liver)

- Change in gut bacteria (microbiota)

A recent review summarized studies that have examined the effect of bariatric surgery on the pharmacokinetics and mechanisms involved in alteration of absorption and/or bioavailability of medications. Most studies were small, and most looked at gastric bypass surgery.

They found that some medications studied had an increased systemic exposure (circulating amount), some meds showed no change in systemic exposure, and others showed decreased exposure. Sometimes the same medication showed lower exposure after surgery in some people but higher exposure after surgery in others. Some medications had sustained changes in exposure over the long term, whereas others had a temporary change in exposure in the first weeks after surgery, which returned to baseline over the longer term.

From the long list of possible mechanisms above, it comes perhaps as no surprise that most bets are off when trying to predict what will happen to the systemic exposure and effect of any particular medication after bariatric surgery. There was very little data after sleeve gastrectomy, which is the other surgery most commonly performed; because the anatomical changes are different from gastric bypass, the alterations in effect of medications could be totally different.

Clearly, more research and understanding is desperately needed in this area. In the meantime, we do our best to adjust meds after bariatric surgery based on clinical evidence of need (eg decrease blood pressure meds if blood pressure is decreasing; use diabetes medication if needed depending on blood sugars), and measuring drug levels where possible (this is possible for only very few meds).

Dr Sue Pedersen www.drsue.ca © 2019

Follow me on Twitter! @drsuepedersen