We know that insulin resistance is a risk factor for stroke. Insulin resistance essentially means that the body is resistant to the effects of insulin, meaning that the pancreas has to work harder to make enough insulin to have the desired metabolic effects. When the pancreas can’t keep up with this resistance, sugars go up, and type 2 diabetes develops. However, many people with insulin resistance do not (yet) have diabetes, as the pancreas is still able to keep up with this higher insulin demand.

In addition to type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance is also associated with hypertension (elevated blood pressure), high insulin levels, high cholesterol, dysfunction of the lining of blood vessels (endothelium), a tendency to clot blood (hypercoagulability and increased platelet reactivity), and inflammation. These factors are all risk factors for stroke. Type 2 diabetes is one of the strongest risk factors for stroke, but insulin resistance is also present in at least half of people without diabetes who have had a stroke or TIA (transient stroke). As blogged previously, obesity is also an independent (stand-alone) risk factor for stroke, and is also associated with insulin resistance.

So how can we reduce insulin resistance, and do these measures reduce stroke risk?

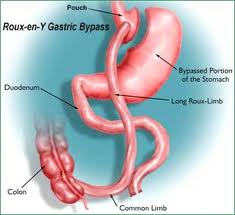

Weight loss in people with elevated weight is extremely important to reduce insulin resistance. To date, only weight loss from bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce stroke risk.

Increasing physical activity (studied in stroke survivors here) reduces insulin resistance, and reduces cardiovascular events in people who have had previous stroke.

The Mediterranean dietary approach can be beneficial to reduce insulin resistance, and reduces risk of cardiovascular events.

GLP1 receptor agonists (GLP1RAs) are medications used to treat diabetes and/or obesity. GLP1RAs reduce inflammation, many reduce weight, and reduce insulin resistance. In people with type 2 diabetes, some GLP1RAs have been shown to reduce stroke risk. In people with obesity without diabetes, the GLP1RA semaglutide (Wegovy) is currently being studied to see if it reduces cardiovascular events (including stroke) in people with prior cardiovascular events (disclosure – I am an investigator in this trial). The new GIP/GLP1RA tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is also currently under study in both people with type 2 diabetes, and people with obesity without type 2 diabetes, to see if it reduces cardiovascular events (including stroke) (disclosure – I am an investigator in the latter trial).

The diabetes medication class called thiazolidinediones reduce insulin resistance, and one of these, called pioglitazone (Actos), has been studied in a trial of 3,876 people without diabetes who had a previous stroke or TIA. After almost 5 years of treatment, pioglitazone reduced the risk of heart attack and stroke by 24% vs placebo. However, pioglitazone is not routinely used in clinical practice, due to the potential for fluid retention (which can exacerbate heart failure), weight gain, risk of macular edema, increased fracture risk, and case reports of bladder cancer. In people with type 2 diabetes, pioglitazone did not reduce cardiovascular events based on its primary endpoint, though a secondary endpoint did meet statistical significance. Due to these data and the side effect concerns above, pioglitazone is not favored in diabetes guidelines around the world. (Note: some other classes of medications used for type 2 diabetes also reduce insulin resistance, but have not been shown to reduce stroke risk.)

BOTTOM LINE: Insulin resistance, obesity, and stroke risk are closely intertwined. Treatment strategies that reduce insulin resistance and weight can be beneficial to reduce stroke risk.

Share this blog post using your favorite social media link below!

Check me out on twitter! @drsuepedersen

www.drsue.ca © 2023